Employees take coffee breaks, skip lunches, answer Slack on “break,” and your payroll team gets the blame when overtime spikes. The real issue: what’s paid and what’s not under the FLSA and state rules. Short rest breaks? Usually paid. A “bona fide meal period”? Unpaid only if the employee is truly off duty. Off-the-clock work? Often payable even when no one punched in. Get this wrong and you risk back pay, penalties, and class actions; especially with automatic meal deductions, interrupted lunches, and time clock rounding.

This guide shows you exactly how to classify breaks vs meal periods, when off-the-clock time counts, how the 20-minute rule works.

First, let’s nail the legal definitions.

What’s the legal difference between rest breaks, meal periods, and off-the-clock time?

Let’s nail the definitions, because pay hinges on them.

Rest breaks: short, paid pauses under federal rules

Short “rest breaks” of about 5–20 minutes are generally paid under the FLSA. They count toward hours worked and therefore toward overtime. Typical examples: a coffee run, bathroom break, or quick reset between tasks. You can’t offset this paid time against other working time. This is the well-known 20-minute break rule.

Meal periods: unpaid only if truly off duty

A “bona fide meal period” (typically 30 minutes or more) is unpaid only when the employee is completely relieved of duty; no phones, no coverage at the desk, no monitoring. If the person keeps working or the meal is interrupted, the meal break becomes paid time. Synonyms matter for policy: “meal break,” “lunch break unpaid,” and “unpaid meal break requirements.”

Examples that kill unpaid status:

-

Call-center agent keeps headset on to take overflow calls.

-

Charge nurse must supervise a unit while “on lunch.”

-

Retail manager must remain at the service counter and assist if needed.

Off-the-clock time: when “not clocked in” is still payable

Under the FLSA, “employ” includes to suffer or permit to work. That means if you know or should know someone is working, it’s likely payable—even if they didn’t clock in. Risk zones include pre/post-shift tasks, system boot-up time, donning and doffing time for required PPE, travel between worksites during the day, and some on-call time compensable when restrictions are tight.

Quick examples to audit:

-

Warehouse staff logging into scanners before shift start.

-

Food processing employees changing into required gear on-site (continuous workday).

-

Techs driving from site A to site B midday.

Do we have to pay for short breaks—and how long is “short”?

Short breaks around 5–20 minutes are hours worked. They’re paid and must count toward overtime. You also can’t “credit” paid breaks against other time, like waiting or on-call.

Two policy tips:

-

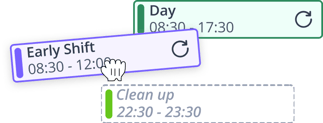

Configure your time system so 5–20-minute breaks default to paid.

-

Show these minutes in weekly hours to avoid overtime surprises.

Unauthorized extensions and “lingering”

If your policy clearly sets break limits and you consistently enforce them, unauthorized extensions beyond the allowed length don’t have to be paid. Document the rule, communicate it unambiguously, and apply corrective action when employees linger. Pair this with system alerts for over-long breaks and manager sign-offs.

Break policy enforcement checklist:

-

State the allowed length (e.g., 15 minutes) and that overages are not authorized.

-

Train leads to intervene and document.

-

Use variance reports to spot patterns by location/shift.

Quick reference table: breaks vs meal periods vs off-the-clock work

| Category | Typical length | Paid status (FLSA) | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest breaks | 5–20 min | Paid; counts toward overtime | coffee, bathroom, brief reset | Can’t offset against other hours. |

| Meal periods | ≥30 min (usual) | Unpaid only if completely relieved | lunch away from duties | Interrupted = paid; no desk coverage. |

| Off-the-clock work | varies | Often payable if you “suffer or permit” | boot-up, donning/doffing, mid-day travel | Your knowledge/benefit controls, not the time clock. |

When is a meal period unpaid, and what kills the unpaid status?

Completely relieved” means hands off work.

Being “completely relieved of duty”

A bona fide meal period (usually 30 minutes or more) is unpaid only when the employee is fully off duty; no calls, no monitoring, no desk coverage. If someone must keep a phone on, watch a queue, or stay available to jump in, the meal counts as hours worked.

Fast policy cues (unpaid meal break requirements):

-

Say explicitly: no work duties, devices off or handed over.

-

Provide coverage so managers aren’t “on duty” during lunch.

-

Reiterate that any work during a meal converts it to paid time.

Interrupted or on-duty meals → pay them

If a meal break is interrupted or the worker stays on duty, pay the entire period and record the reason. Keep a simple missed/short meal log with fields for date, shift, minutes short, and cause (e.g., patient event, peak queue, coverage gap).

Automatic meal deductions: proceed with caution

Automatic meal deduction settings can trigger back-pay claims if they deduct time when meals were not truly off duty. Anchor on the FLSA principle: only bona fide meals are not hours worked. If you keep auto-deducts, require employee attestations or manager exceptions and run audit reports to catch frequent overrides.

Guardrails for auto-deducts:

-

End-of-shift attestation: “I had a 30+ minute uninterrupted meal.”

-

Real-time exception flow when meals are missed/short.

-

Weekly audit: variance report of deductions vs. attestations.

What counts as off-the-clock work we still must pay?

If you benefit from the work, it’s probably payable.

Pre/post-shift tasks and boot-up time

Work done before or after a scheduled shift can be compensable, even if nobody punched in. Examples: booting a POS or laptop, loading routes, staging equipment, or closing tasks after clock-out.

Implementation tips:

-

Add a pre/post-work question on clock-in/out.

-

Require manager approval for added minutes.

-

Report weekly on patterns by team or device.

How should we set policies, timekeeping, and audits to stay compliant?

Write it down, track it, prove it.

Clear break/meal policy with attestations

Spell out paid rest breaks vs bona fide meal period rules, forbid off-the-clock work, and require end-of-shift attestations for missed or short meals. Add examples (interrupted meal, on-duty meal, on-call constraints) so supervisors apply the policy consistently.

What to include:

-

Definitions (paid rest, unpaid meal if completely relieved).

-

A no-work directive during meals.

-

Attestation text on clock-out and a simple exception path.

Timekeeping design: no auto-deduct without safeguards

Avoid blanket automatic meal deduction unless you pair it with protections. Use exception logs, manager approvals, alerts when meals not taken, and periodic reviews of time clock rounding rules and grace periods.

System guardrails:

-

Flag shifts with no recorded meal or <30 minutes.

-

Require a reason code (busy period, coverage gap).

-

Route exceptions to a manager for same-pay-period approval.

Recordkeeping & reporting

Keep detailed recordkeeping for breaks: scheduled vs. taken meals, rest timing, missed/short counts, premiums paid, and exception narratives. Run variance reports weekly and quarterly audits; this is especially useful in Washington healthcare settings that require tracking missed/waived breaks.

Audit pack (ready-to-export):

-

Policy + manager training logs.

-

Break exception list with approvals.

-

Quarterly rollup of missed/rest/meal and premiums.

What special cases trip up employers?

Edge cases cause most claims—prepare for them.

Remote/hybrid: availability creep

If employees answer Slack/Teams during lunch, that interrupted meal break becomes paid. After-hours pings can morph into off-the-clock work. Set do-not-disturb norms, pause notifications, and require attestations if lunch was cut short.

Shift leaders “covering” during lunch

If a lead or manager remains responsible for the floor, the meal is on duty and paid—even if they sit in the break room. Provide floaters or cross-coverage so leaders are completely relieved. Train supervisors to classify these correctly and avoid accidental off-the-clock gaps.

Manager cue card:

-

“Do you still hold responsibility during lunch?” If yes, mark paid.

-

“Was the meal interrupted?” If yes, pay full period and log it

Minor employees & healthcare rules

Minors and healthcare workers often have stricter state meal and rest break laws. In Washington, for example, L&I guidance sets special standards and healthcare reporting for missed/waived breaks. Link to your state agency pages in the handbook and teach managers the differences.

Playbook add-ons:

-

Maintain a minors/healthcare appendix with state links.

-

Audit these groups quarterly for timing and documentation.

Streamline breaks, meals, and payroll in one place

Shiftbase connects employee scheduling, time tracking, absence management, and payroll so FLSA rules translate into clean, provable records. Configure the 20-minute break rule, set unpaid meal break requirements, and block risky automatic meal deduction without an attestation. When off-the-clock work pops up (boot-ups, don/doff), Shiftbase prompts for minutes and routes them for approval.

Why it helps now:

-

Schedule meals and rest into shifts and enforce coverage.

-

Capture “missed/short/interrupted” meals with one tap.

-

Roll break data into overtime and payroll exports (Excel or your provider).

-

Keep recordkeeping for breaks audit-ready with exception logs and variance reports.

-

Integrate with third-party tools to keep hours worked, leave balances, and overtime aligned.

Result: fewer disputes, compliant payouts, and a single source of truth across locations.

Try it free: Get full features for 14 days. Start your trial.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Yes. Short rest breaks (~5–20 minutes) are paid and count toward hours worked and overtime.

-

Only if they’re completely relieved of duty. If they monitor phones, assist customers, or work, it’s paid.

-

Risky without safeguards. Use prompts/attestations to reverse deductions when meals are missed or interrupted. Anchor to FLSA “hours worked.”

-

If required gear is integral to the job, related donning/doffing (and related walking/waiting after first principal activity) is compensable.

-

States can be stricter; .g., CA meal/rest rules and WA healthcare reporting. Follow the most protective rule.

-

It depends on the restrictions. If the constraints significantly limit personal time, it’s likely compensable.