Biometric timekeeping is reshaping how employers track employee hours. This guide explains the core technologies, the real benefits, the pitfalls to avoid, and how to roll it out responsibly.

What is biometric timekeeping?

Biometric timekeeping is simply using a person’s physical or behavioural traits to clock in and out, instead of cards, PINs or paper.

Common biometric identifiers for time and attendance

| Method | How it works | Typical use |

|---|---|---|

| Fingerprint | Matches ridge patterns to a stored template | Offices, retail, hospitality |

| Facial recognition | Maps facial geometry via camera | Contactless kiosks, mobile clock-ins |

| Iris | Authenticates from patterns in the coloured iris | Labs, defence, high-security sites |

| Voice | Verifies voiceprint & speech traits | Hands-free or remote scenarios |

| Hand geometry | Measures hand size/shape | Industrial environments |

How biometric time clocks work

In most workplaces, a biometric time clock or biometric attendance system uses one of a small set of identifiers:

-

Fingerprint templates – a scanner measures points on the fingerprint and turns them into a mathematical template, not a raw image.

-

Facial recognition – a camera maps key points on the face and builds a face template for a “facial recognition time clock”.

-

Iris or palm-vein patterns – less common, usually in high-security environments.

-

Voice or keystroke patterns – sometimes used in call centres or highly remote work.

A typical biometric time clock works in three simple steps:

- Enrolment – the employee presents their finger or face once to create a secure template linked to their profile.

- Clocking – at each shift, they present the same trait; the device compares the live scan to the stored template.

- Recording – if there is a match, the system logs a precise clock-in or clock-out time in the time and attendance software.

Modern systems are designed so the template cannot be reverse-engineered back into a recognisable fingerprint or face and are stored in encrypted form on the device or in a secure cloud environment.

When biometric time and attendance systems make sense

Biometric time clocks make the most sense when fraud risk, access control and compliance costs are high enough to justify the extra privacy risk.

-

“Buddy punching” is when one worker clocks in for another. It is still one of the most common forms of time theft. A survey of US hourly workers found that 16% admitted to buddy punching, which could add over $373 million a year to payroll costs if just 15 minutes are added per shift.

Because biometric attendance systems link each clock-in to a unique physical trait, it becomes very hard for colleagues to cheat the system. That does not remove the need for good scheduling and supervision, but it can significantly reduce casual time theft and send a clear message about fairness.

-

For many managers, the biggest benefit of biometric timekeeping is not just stopping fraud; it is cleaner data:

-

Clock-ins and clock-outs are recorded to the minute, with less manual correction.

-

There is a clear history if you need to investigate overtime claims or underpayment complaints.

-

Approved hours can be exported straight into payroll, reducing re-keying errors and compliance risks.

When staff know the system is accurate and consistent, disputes about “who was here and when” tend to drop, which saves time for both HR and line managers.

-

-

Biometric time and attendance systems can also double as access control tools, especially in settings with high security or safety needs (for example, labs, healthcare, logistics hubs or cash handling).

They are most useful where you need both:

-

Strong identity checks at doors or zones; and

-

Reliable time data for payroll or working-time compliance.

However, in ordinary offices or low-risk environments, a biometric time clock might be more intrusive than necessary, especially under UK and EU data protection rules.

-

Are biometric time clocks legal in 2026?

Legality is less about the device itself and more about how, where and why you use it, plus how you protect biometric data.

United States – where biometric time clocks are highest risk

In the US there is no single federal law just for biometric time clocks, but biometric identifiers (such as fingerprints and faceprints) are often treated as sensitive data under state privacy laws. Some states, such as Illinois, Texas and Washington, have specific biometric privacy statutes, while others include biometrics within broader consumer or employee privacy acts.

The key takeaway for managers is:

-

You normally need clear written notice, a lawful purpose, and a retention and deletion policy.

-

In some states, employees can sue directly if you get this wrong.

-

City-level rules and union agreements may add further limits.

Because rules differ, employers should always get local legal advice before rolling out a biometric fingerprint time clock across multiple US states.

United Kingdom – biometrics as “special category” + ICO enforcement

In the UK, biometric data used to uniquely identify a worker is “special category data” under the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018. This means you need:

-

A lawful basis (for example, legitimate interests or legal obligation); and

-

An extra condition for special category data (often explicit consent), plus a clear, proportionate reason.

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) published final Monitoring workers guidance in 2023. It stresses that using biometric data for time and attendance will rarely be justified in ordinary workplaces unless you can show it is necessary and proportionate and that less intrusive methods would not work.

For UK employers, the practical message is:

-

Run a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) before introducing any biometric attendance system.

-

Be ready to explain why biometrics are needed, and why swipe cards or PINs are not enough.

-

Offer a genuine non-biometric alternative for staff who object.

Before you roll out: should you even use a biometric time clock?

Before you buy any device, step back and ask whether a biometric time clock is really needed for your workplace.

Necessity, proportionality and less intrusive alternatives

Under modern data protection rules, especially in the UK and EU, you should only use biometric timekeeping if it is necessary and proportionate to the problem you are trying to solve. The ICO’s 2023 Monitoring workers guidance makes clear that you must consider less intrusive options (such as swipe cards or app-based clock-ins) before turning to biometrics.

A simple way to test necessity is to ask: what goes wrong if we use a non-biometric option instead? If the only impact is “slightly more admin”, biometrics will be hard to justify; if it is “we cannot meet legal security standards or stop serious fraud”, you have a stronger case. Whatever you decide, record your reasoning in writing so you can show you have thought about privacy, not just convenience.

High-security vs ordinary workplaces: different justification thresholds

Biometric time and attendance systems are easier to justify in high-security environments, such as data centres, laboratories, healthcare settings with controlled drugs, or cash-handling sites. In these locations, it is plausible to say that card-sharing or PIN-sharing could seriously undermine safety, confidentiality or regulatory duties.

In ordinary offices, retail or leisure settings, regulators are far more sceptical. The ICO’s enforcement action against Serco Leisure in 2024 found that facial recognition and fingerprint scanning for staff clock-ins were not necessary or proportionate where swipe cards and fobs would have worked.

If you operate a mixed estate, you may end up with different solutions: biometrics in genuinely high-risk zones, and non-biometric timekeeping elsewhere.

How to run a quick DPIA / risk assessment just for timekeeping

A Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) does not need to be a 50-page legal document. For biometric time clocks, a focused 6–step DPIA usually works well:

- Describe the purpose – for example, “prevent buddy punching and control access to controlled areas”.

- List the data – which biometric identifiers, where stored, and who can access them.

- Map the risks – privacy harms if data is misused, breached, or used for broader monitoring.

- Consider alternatives – cards, PINs, app clock-ins with GPS; explain why each is or is not sufficient.

- Define safeguards – encryption, strict access control, clear retention and deletion rules, staff training.

- Decide and document – proceed with biometrics, adjust the plan, or choose a less intrusive method.

Biometrics vs other timekeeping options: choosing the right tool

Here's how you decide whether a biometric time clock is the best fit, or whether simpler tools will do the job.

Biometric time clocks vs PIN/badge vs app-only solutions

Most modern time and attendance systems, including biometric attendance machines, sit alongside PIN pads, swipe cards and app-based clock-ins. The trick is to match risk level and culture to the right option.

CIPD and other professional bodies highlight that employers should keep monitoring methods proportionate and transparent, and should not automatically pick the most invasive technology if a lighter option meets the business need.

When to stay with non-biometric time tracking (and still cut fraud)

You may decide that a biometric time and attendance system is overkill for your environment, especially after looking at ICO and EEOC guidance. That does not mean you are stuck with paper.

You can still reduce time theft and errors by:

-

Using geofenced app clock-ins so staff can only clock in from authorised locations.

-

Setting clock boundaries and rounding rules (for example, auto-clock-out after a certain time, or rounding late punches) so your timesheets reflect policy.

-

Enforcing clear rules on late arrivals and no-shows, supported by reliable digital records rather than guesswork.

In many offices, shops and leisure settings, a non-biometric geofencing time clock plus good policies will be easier to justify to workers and regulators than a facial recognition time clock at every door.

How Shiftbase connects with biometric time clocks (without creating a compliance headache)

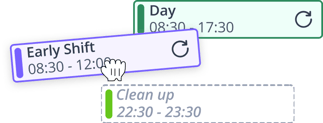

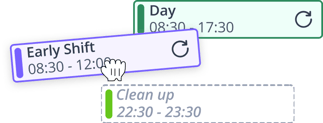

Shiftbase is designed to collect working hours from different sources: employees can clock in via the mobile app, web browser, a kiosk-style punch clock terminal, or connected on-site time clock hardware. Through integrations with hardware partners (for example, EasySecure and Datafox), Shiftbase can pull time data from terminals that may use badges, PINs or biometric identification and sync those punches directly into your digital timesheets.

You can manage punch clock rules centrally in Shiftbase (such as rounding, auto clock-out and department-specific settings) so the same policies apply whether staff clock in with a biometric time clock at the warehouse or an app in the field.

That makes it easier to align your retention rules, audits and compliance checks across different devices, and to offer non-biometric alternatives for employees who need them, without losing the benefits of automated timekeeping.If you want to see how biometric and non-biometric timekeeping can live happily in one system, you can try Shiftbase for free for 14 days and test it with your own teams and devices.

- Easily clock in and out

- Automatic calculation of surcharges

- Link with payroll administration

Frequently Asked Questions

-

You can make use of a biometric time clock a condition of work if you have implemented it lawfully, explained it clearly, and you are not ignoring protected rights (like disability or religion). In practice, regulators and courts expect you to show that the system is necessary, legally compliant, and that staff have been properly informed, not ambushed

-

If an employee refuses a fingerprint or facial recognition time clock because of a disability (for example, a skin condition that makes scanning painful or unreliable) or a sincerely held religious belief, you have a duty in many jurisdictions to consider a reasonable accommodation. In the US, Title VII and the ADA both require employers to adjust policies where possible, unless that would create an undue hardship.

-

A facial recognition time clock on a mobile app, often combined with GPS or geofencing, can be very attractive for monitoring hybrid and field teams. But from a privacy point of view, you are now processing biometric + location data, which is about as sensitive as it gets. Regulators like the UK ICO treat this as high-risk monitoring that normally requires a DPIA, strong transparency, and clear limits on when and where tracking happens.